By Lenese Herbert

on May 17, 2021 at 4:20 pm

Update (May 18, 8:15 p.m.): This article has been expanded with additional analysis.

On Monday, the Supreme Court released its opinion in Caniglia v. Strom, which unanimously held that a lower court’s extension of Cady v. Dombrowski’s “community caretaking” exception into the home defied the logic and holding of Cady, as well as violated the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement. With the court’s unanimity in Caniglia, the home remains the most sacred space under the Fourth Amendment; its sanctity literally houses its privilege. Sans warrant, exigency or consent, governmental search and seizure within it is unconstitutional.

During an August 2015 argument with his wife, Edward Caniglia offered her one of his unloaded guns and requested that she put him out of his misery. Instead, she threatened to call 911. After the couple’s argument continued, she left the marital home to overnight at a hotel. When she returned the next day, she enlisted Cranston, Rhode Island’s police department to perform a wellness check on her husband. They did. They also arranged transportation for Edward to obtain a psychiatric evaluation at a local hospital. He agreed to go, but only after officers purportedly agreed not to confiscate his weapons. However, as soon as he left, officers — apparently by deceiving his wife — entered the Caniglia home and seized Caniglia’s handguns and ammunition. Caniglia sued, alleging that the officers violated his Fourth Amendment rights. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 1st Circuit sided with the officers by relying on Cady, a 1973 decision that upheld the warrantless “caretaking” search of a car that had been in an accident.

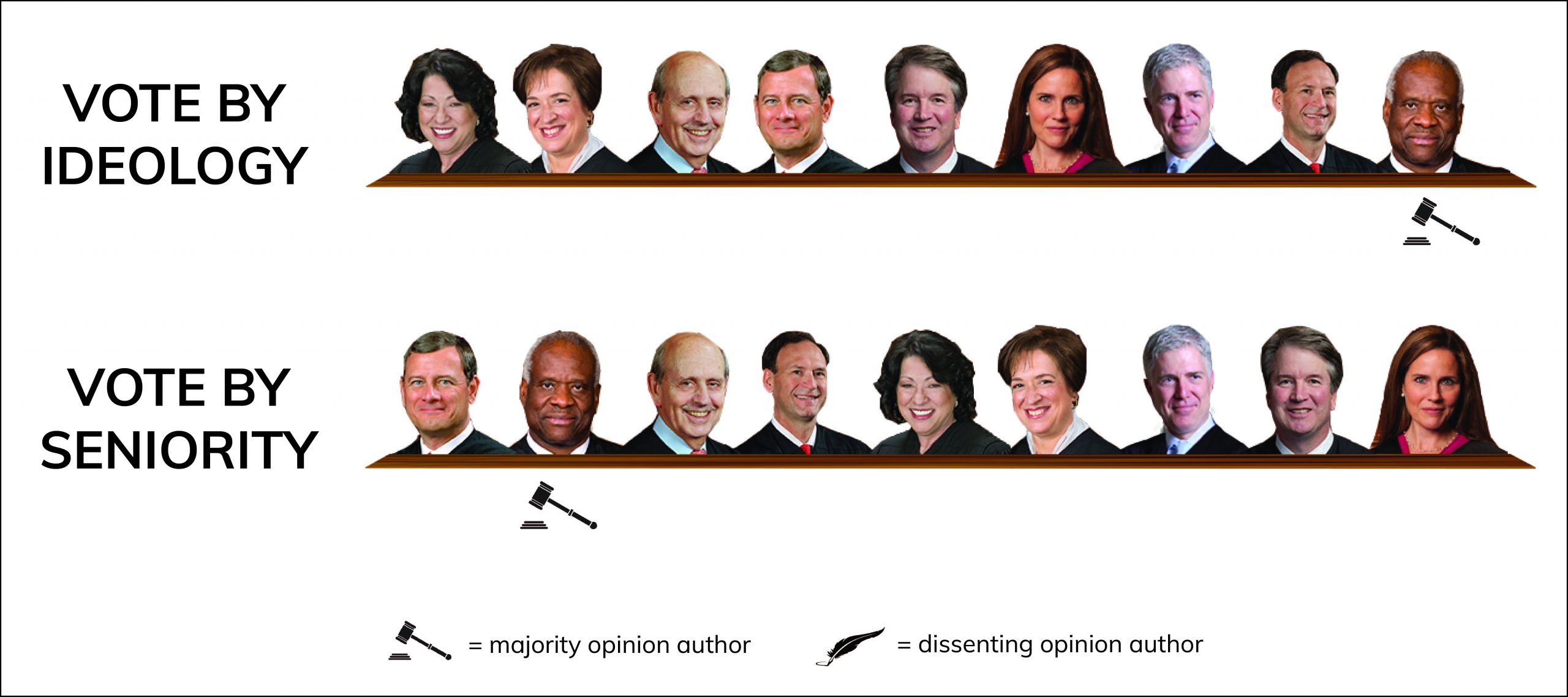

The court’s opinion, written by Justice Clarence Thomas, was devoid of the fearsome, compelling specter raised in the briefing and during argument regarding the potential for troubling eventualities — for instance, that Caniglia may have harmed himself or his wife (or, perhaps, other innocent/intervening victims). A pithy four pages “long,” the opinion was unanimous and unambiguous: If police do not have the homeowner’s consent, an “exigent” circumstance, or a judicial warrant authorizing a search, then no version of Cady’s car exception applies to police entry into the home under the Fourth Amendment. “What is reasonable for vehicles is different from what is reasonable for homes,” Thomas wrote.

As always with realty – and, per Caniglia, the court’s Fourth Amendment jurisprudence — location matters. Specifically, the location of Cady’s warrantless search and seizure – a post-accident, routine search of an intoxicated, off-duty officer’s damaged and impounded car — simply cannot compare to a search of and seizure within a home. Governmental searches of vehicles regularly occur via exceptions to the Fourth Amendment’s warrant requirement; a myriad of decisions have constitutionalized warrantless searches of vehicles, their compartments, their containers and even their occupants. Not one of these warrantless exceptions is available for the home.

Accordingly, caretaking under Cady is not carte blanche for police to search or seize within the home, nor do their “caretaking” duties create a “standalone doctrine that justifies warrantless searches and seizures in the home,” Thomas wrote. Cady, itself, he noted, drew an “unmistakable distinction between vehicles and homes,” constitutionally embedding the exception outside the home.

That police may engage in a myriad of “civic” community caretaking functions did not move the court off its jurisprudential bright line. Certainly, such functions give texture to the modern, sometimes complex, role of policing. They do not, however, supplant the constitutional sanctity of the home. Accordingly, the Caniglia court declined the opportunity to expand Cady’s “community caretaking” exception and permit warrantless entry into the home.

The court vacated the 1st Circuit’s judgment and sent the case back to the lower court for further proceedings consistent with the opinion.

Notwithstanding the court’s unanimous decision, there were three concurring opinions. Though ranging in length (from one paragraph to longer than the court’s opinion), they, too, evidenced unanimity, given that each identified the jurisprudential play in what defines an “emergency” or “exigent circumstances.”

In a single concurring paragraph, Chief Justice John Roberts, joined by Justice Stephen Breyer, noted that the Fourth Amendment does not prohibit warrantless entries “when there is a ‘need to assist persons who are seriously injured or threatened with such injury.’” Warrantless entries into the home are justified where there is “an objectively reasonable basis for believing that medical assistance was needed, or persons were in danger.”

Similarly, Justice Samuel Alito’s concurrence seemed to redefine determinative concepts. First, it minimized “community caretaking” as a Fourth Amendment category, stating that “there is no overarching ‘community caretaking’ doctrine” nor a “special Fourth Amendment rule for a broad category of cases involving ‘community caretaking.’” Hmmm.

Perhaps given the Caniglia court’s unambiguous limitation of the “community caretaking” exception to cars, Alito saw the fruitlessness of further beating a dead horse (or rescuing a treed cat?). Whatever the reason, his concurrence warned the court that it “should not assume that the Fourth Amendment’s command of reasonableness applies in the same way to everything that might be viewed as falling into this broad category” of cases (which, apparently and per his concurrence, does not even exist). What does seem to exist are “searches and seizures conducted for non-law-enforcement purposes.” Alito cites as examples states’ suicide prevention and “red flag” laws, which allow police to enter a home and seize weapons to be used for the purpose of suicide or inflicting harm “on innocent persons.” Strangely, Alito criticized Caniglia for not taking on these laws before the court, yet praised the court for not engaging or deciding the constitutionality of these laws pursuant to the restrictions of the Fourth Amendment, which “may or may not be appropriate for use.” But, if Caniglia failed to properly raise these and a unanimous Court failed to mention them at all, why did Alito’s concurrence see fit to address them at length?

But it is Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s concurrence – now that Caniglia expressly limits the “community caretaking” exception to cars — that plainly portends what the other concurrences make cryptic (Roberts, joined by Breyer) or confusing (Alito):

[T]he Court’s exigency precedents, as I read them, permit warrantless entries when police officers have an objectively reasonable basis to believe that there is a current, ongoing crisis for which it is reasonable to act now … If someone is at risk of serious harm and it is reasonable for officers to intervene now, that is enough for the officers to enter.

Again: this is not what Caniglia, or any other court decision, has ever held. Yet, per Kavanaugh’s concurrence, the court, going forward, is now perfectly poised to redefine the “exigent circumstances” doctrine as applied to emergency aid situations anew, expanding the exception’s imprimatur in ways that would allow warrantless, in-home police searches and seizures. Relying upon the pitched examples heard at argument regarding the parade of horribles that included suicide threats, as well as absent or fallen senior citizens, Kavanaugh queried: If officers knock on the home’s door but do not receive a response, “[m]ay the officers enter the home?” His answer: “Of course.”

Some may ignore Kavanaugh’s concurrence, allowing it to represent yet another example of why the late Justice Antonin Scalia waxed poetic about the utter freedom when one writes lone dissents. But this is not a dissent; it is a concurrence. Its analysis is no mere dicta; rather, it may better be characterized as “dicta dentata,” i.e., dicta with teeth, given what Caniglia’s unanimity and the drumbeat of the concurrences augur.

Wait: Did it suddenly get chilly in here? Someone must have just opened an Overton Window.